Circulating Sydney - Propaganda & the Self-Determination League for Ireland of Australia, 1921-22

By Steven Egan

In studies of the global Irish revolution, the establishment of a series of Self-Determination for Ireland Leagues in the dominions of the British Empire has largely been overlooked. These transnational organisations successfully rallied solidarity, raised finances and applied political pressure across the Imperial world to assist in the campaign for Irish independence. Whilst the Leagues were successful in Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand, and even in Great Britain itself, the Self-Determination League for Ireland of Australia (SDILA) arguably enjoyed the greatest success.

Whilst it is difficult to definitively credit any individual wing of the Self-Determination League, the collective discontent which they helped generate in the Dominions ultimately had a tangible impact on events back home. In June 1921 as the British Government, once again, failed to bring de Valera to the negotiation table, the Melbourne Advocate reported that David Lloyd George had bemoaned that ‘Downing Street is now governed by the Dominions’ on matters of Irish affairs. For those sympathetic to Ireland in Australia, these words were hailed as a moment of victory and proof that inter-Imperial relations had changed forever.

After Art O’Brien’s success in establishing a Self-Determination League in Great Britain in 1919, under de Valera’s instruction, Katherine Hughes, established the Self-Determination for Ireland League of Canada and Newfoundland with Ulsterman Robert Lindsay Crawford in May 1920. Yet even at this early stage, Hughes was already corresponding with de Valera about her next challenge: Australia.

In late-1920, Hughes was redeployed to Australia to reproduce another Self-Determination League for Ireland and arrived sometime in January 1921. As part of the broader global mission, de Valera had also appointed Osmond Grattan Esmonde to organise New Zealand – though the plan quickly went wrong when Esmonde was detained upon arrival. Consequently, the burden of organising both dominions fell to Hughes.

Upon her arrival, Hughes found Irish-Australia to be in a similar condition to that of Canada prior to the establishment of their Self-Determination League. Whilst various Irish societies were in operation in Australia, they had been unable to reconcile their differences in order to produce a unified front in the support of Irish independence.

This had not been for a lack of trying though. The Cork-born Archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix had been unsuccessful in creating an umbrella organisation two years prior, when the Archbishop spearheaded the Australasian Irish Race Convention in Melbourne. Whilst the event garnered plenty of attention across the Irish world, it had been unable to unify Irish-Australians and New Zealanders behind a common standpoint on Ireland’s future.

Whilst prominent figures, such as Mannix, supported an Irish Republic independent of the British Empire, this was a minority stance. Even at the height of the conflict in Ireland, the majority of Irish-Australians were convinced that dominion status was sufficient to alleviate the plight of British rule in Ireland, whilst maintaining the integrity of the Empire of which they were proud to be a part.

Under Hughes’ guiding influence, the Self-Determination for Ireland League of Australia (SDILA) was informally established at a small collective meeting on 18 February 1921, before being formally launched to much acclaim, at the Sydney Town Hall on 26 February. Neal Collins, an Ulster-born solicitor, quickly emerged as the state president of the new League, with Rev. Albert Rivett and Lieutenant Peter Gallagher serving as vice presidents.

Adapting the Canadian League’s model to better suit Australian federalism, Hughes mandated that the Sydney branch would be at the core of the New South Wales (NSW) section, before travelling onto Melbourne where the Victoria section was established on 1 March.

Until the end of April, Hughes continued to tour the remaining states and territories of Australia, cementing the League as a nationwide organisation before departing for New Zealand. Within four months of the first branch being established, 369 branches were formed nationwide, with membership figures reaching approximately 34,000.

Whilst her time in Australia was relatively brief, the organisation that she helped establish bore her distinctive trademarks. Hughes, whilst a supreme organiser, had also proven to be a gifted writer throughout her previous undertakings in North America. Given that Hughes could be deported for sedition if she spoke publicly on Ireland, literature became of paramount importance for disseminating the message of the fledgling organisation.

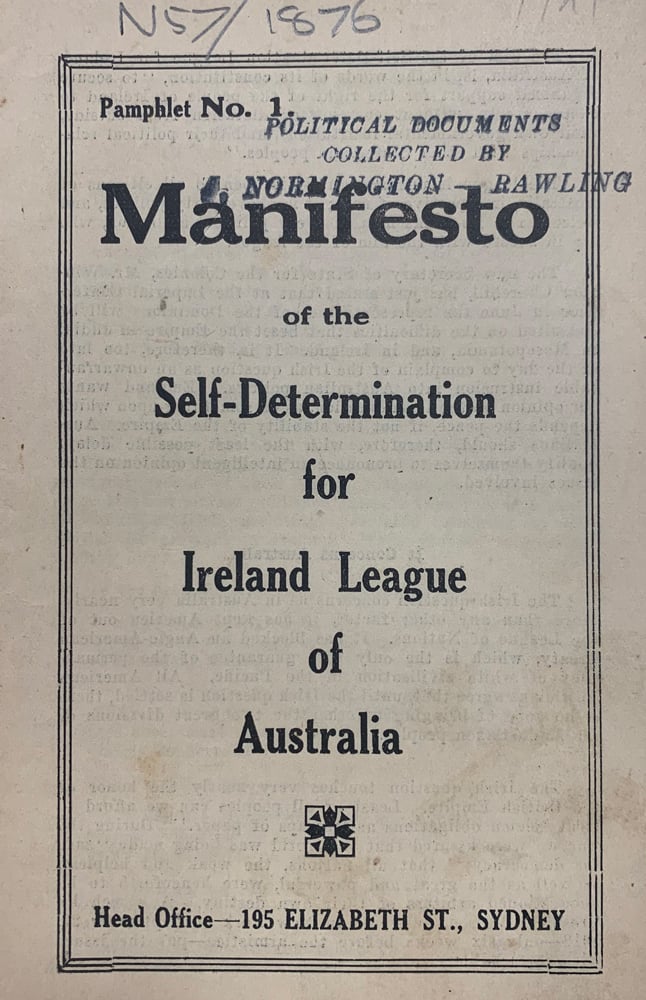

Unlike Canada, the Australian organisation enjoyed substantial financial backing and as a result could afford to produce its own literature. Having secured its headquarters, at 195 Elizabeth Street, by late-April, the NSW section began publishing and circulating its own material on the Irish question within Sydney and its surrounding areas.

In concluding their Pamphlet No. 1 (manifesto), the Sydney SDILA stated that ‘many of us who belong to the League are Protestants, many again have in our veins not a drop of Irish blood; but as good Australians, we appeal to all our fellow-countrymen to come out into the open and say that, after all the sacrifices made by our boys in the cause of freedom, this attempt to dragoon the Irish nation must cease.’ (Image: Noel Butlin Archives Centre, Australian National University: J Normington Rawling collection, N57-1876, Self-Determination for Ireland League of Australia, Victorian Section, 'Australia's interest in Ireland's claim to self-determination', 1921)

By the end of 1921, at least eight separate pamphlets were produced. A short-lived newspaper, The Small Nation, which was printed in Melbourne, also circulated SDILA branches and almost certainly reached branches in NSW. The Sydney pamphlets, such as No. 3 on Irish Disloyalty and No. 4 on The Black and Tans, frequently cited intense testimonial responses from English Protestant commentators and politicians in order to deflect the allegations of seditious disloyalty and sectarianism thrown at the League.

The first published pamphlet outlined the national manifesto of the League. The document immediately proclaimed that the SDILA wanted to ‘secure organised support for the right of the people of Ireland to choose freely, without coercion or dictation from outside, their own governmental institutions and their political relationships with other States and peoples.’

This catch-all principal of the SDILA explains much of the organisation’s success; by not explicitly giving a view on the solution to the Irish question, the League maximised its base of support by not alienating Republicans or Dominion Home Rulers. Furthermore, the manifesto placed great emphasis upon Wilsonian conceptions of freedom and self-determination – ideas which had become an integral part of Australian national identity after the First World War.

As a result, the SDILA found that invoking the sacrifice of Australian service personnel, with the cause of Irish self-determination, to be an extremely effective approach at winning support beyond the Irish-Australian community. In turn, this greater base of support gradually allowed the SDILA to become increasingly vocal in supporting a Dominion Home Rule settlement for Ireland.

Whilst invoking the sacrifices of the Australian war dead was an effective method in garnering support, it also attracted outrage from those opposed to the SDILA. In October 1921, the SDILA clashed with one of Sydney’s most prominent Imperial ‘Loyalty Leagues’, the King and Empire Alliance (KEA).

The KEA had first emerged in Queensland during the Red Flag Riots of 1919 as a means to supress ‘Bolshemakia’ but had spread to NSW in 1920 as a means of suppressing John Storey’s Irish-sympathising Labor Party.

After Labor’s shock victory in the NSW State Elections in 1920 and the success of the SDILA in Sydney in 1921, John Stinson, the president of KEA, aided by Sir Charles Rosenthal, a respected WWI field-commander and Herbert Brookes, the main financier of the KEA, went on the offensive against the SDILA in the KEA members’ journal.

Local politician Thomas John Ley questioned the SDILA’s loyalty to Australia in the July edition of the KEA’s monthly journal. He argued that ‘England has granted Home Rule to the Southern Irish, as well as to the Northern…They do not want Home Rule. If they did, they have only to accept it.’ Ley concluded that should the Irish ‘still refuse to accept Home Rule…the criminals responsible must, for the sake of civilisation, be brought swiftly and surely to account.’

Ley’s remarks, amongst the commentary of other contributors, invoked such a reaction that the SDILA published Pamphlet No. 7 directly to members of the KEA addressing the aspersions. The pamphlet predominantly focused on the allegation that the SDILA was an inherently disloyal organisation – something which Neal Collins and his state council denied – how could the SDILA be disloyal to the Empire when the League simply advocated for Ireland what loyal Australians already enjoyed?

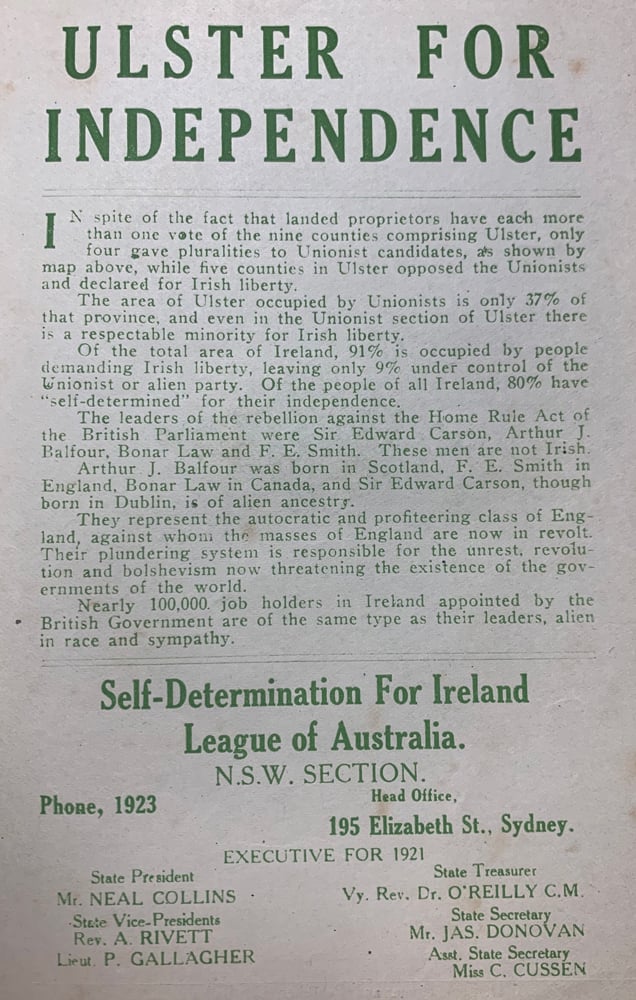

In late-1921, the SDILA published Pamphlet No. 8 ‘Ulster for Independence’ their shortest publication. The League emulated the same methodology used in Britain and Ireland by highlighting the 1918 General Election results and discrediting the behaviour of Sir Edward Carson and other Unionists in order to delegitimise partition as a solution to the Irish question. (Image: Noel Butlin Archives Centre, Australian National University: J Normington Rawling collection, N57-1880, Self-Determination for Ireland League of Australia, 'Ulster for independence', 1921)

In late-1921, the SDILA published their final pamphlet of the year – Ulster for Independence – their shortest pamphlet which simply mocked the notion that Ulster could be given independence in any settlement the Irish plenipotentiaries might agree to; the pamphlet was a timely reminder that to Irish-Australians, Ireland was one, indivisible unit. Ultimately, partition was a bitter pill which the League had to accept – though the League published the thoughts of prominent Irish-Sydneysider, Fr Maurice O’Reilly, in The Catholic Press on how economic considerations would certainly compel Irish unity shortly.

With Dominion status won at the negotiation table and ratified by the representatives of the Irish people in Dáil Éireann in January 1922, the majority of Irish-Australian commentators and their allies were placated. The climax of the global Irish Self-Determination League movement, the Global Irish Race Conference, which took place between 21-28 January in Paris ultimately was severely checked by the accession of the Treaty. The event, which Katherine Hughes had planned for since her return from the Antipodes, ultimately descended into a display of abysmal civil war politics which the Australian delegates had no interest in engaging with.

With their objectives mostly satisfied, the SDILA’s reason d’être had been fulfilled. The League slowly began to break apart, being formally dissolved in 1924. Whilst the SDILA in Sydney was short lived, the organisation had played a significant role in the national Australian picture, being responsible for the most efficient section of the SDILA’s propaganda machine at the height of the Irish revolution. The impact which this group made, both domestically within Australia and coupled with efforts of others around the world, weighed heavily on the minds of Lloyd George and the British negotiation team during the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations.

Steven TM Egan is a doctoral researcher at Queen’s University Belfast. His research primarily examines the engagement and influence of the British Dominions on the process of partitioning Ireland, 1919-25.