Blood on the Flag: Seán O’Casey’s Dublin in the Shadow of Revolution and Civil War

By Ed Mulhall

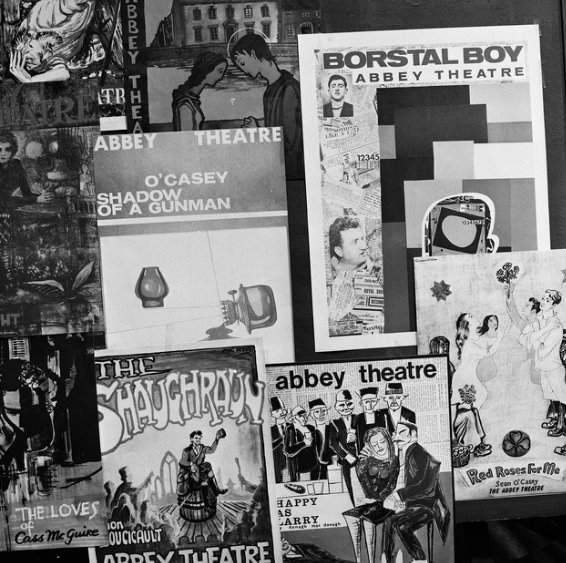

On Thursday, 12 April 1923, The Shadow of a Gunman by Seán O’Casey was first performed on the stage of the Abbey Theatre, Dublin. It was the first play by O’Casey, then aged 43, to be accepted by the Abbey and the first time he used O’Casey as his name. Originally titled, On the Run, it had been submitted by O’Casey immediately after a previous play, The Crimson in the Tricolour, had been finally rejected after a year’s wait. The change of title to The Shadow of a Gunman, recommended by the play’s director Lennox Robinson, sharpened the edge and resonance of the play for its time and caught perfectly the combination of satire and tragedy that were at the heart of the work. For this first performance came under the shadow of the Civil War, still waging after almost ten months of hostilities.

That morning’s newspapers reported details from the inquest into the death of Liam Lynch, the leader of the anti-Treaty, Irregular IRA. Lynch’s body had been left on a road in the Comeragh mountains of County Waterford following a gun battle with the Free State government’s National Army forces, two days earlier. There were reports that Lynch had been in the area meeting other leaders of the anti-Treaty side including Dan Breen and Mary MacSweeny. The inquest heard that Lynch, before dying of his wounds in Clonmel hospital, had expressed the wish to be buried in Fermoy, Co. Cork. All the papers reported a statement from the Army general headquarters confirming the execution of six men in Tuam following the verdict of a military tribunal. The convictions for possession of arms and ammunition followed a National Army operation in North Galway on February 21st which saw one man dead and eighteen arrested. There was also a report on an inquest into the death of two soldiers in Headford following an attack on their barracks the previous Saturday. Throughout the papers there were other accounts of arrests, house burnings or attempted burnings, and violent incidents throughout the country including the hijacking and burning of the Wexford passenger train.

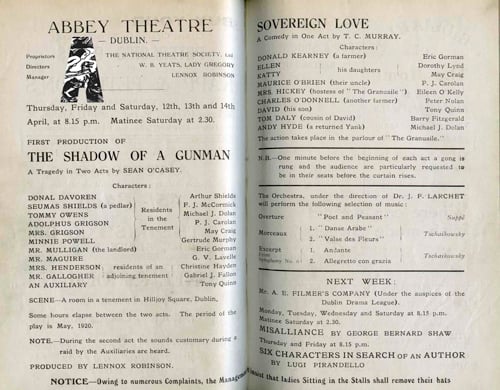

Even for patrons attending the performance in the Abbey there was no escaping the tension of the times. The entrances to the theatre were guarded by National Army soldiers, as they had been since March when the IRA had demanded the closure of all theatres and cinemas to protest against the government executions and in solidarity with anti-Treaty prisoners on hunger strike. Following discussions with government ministers, the Abbey had stayed open with an assurance from Minister Desmond Fitzgerald that the Army would provide security. (There were concerns for the safety of the Abbey director W.B. Yeats who as a Free State Senator was a potential target.) In the programme for the production of the Gunman the director Lennox Robinson warned that in the second act ‘sounds customary to a raid by the Auxiliaries are heard’ so that the audience would not become alarmed that there was a dangerous incident occurring outside the theatre.

Given this context and with the play’s title and its description as a ‘tragedy in two acts’ it was not surprising that the Abbey management was wary of its reception and presented it as part of a double bill, for three days only, at the end of its Spring season. The theatre was just two thirds full on opening night. Then there was the content of the play itself - its stark realistic setting in a tenement, its sharp satiric edge and most of all its uncompromising approach to the national struggle and the terror of the times. But such was the wit and irony of the dialogue, the strength of characterisation and the skill of performance that the audience was engaged and enthusiastic in its reception.

The reviewer, Jacques, from the Irish Independent captured the occasion noting that the audience ‘revelled in the realism’:

‘The dialogue is scathing. The more it was so, the more the audience cheered and laughed. There were only snatches of silence while the pedlar philosophises from his bedclothes about the “rotten” country. “Nowadays” he remarks, instead of counting their beads, they’re counting bullets’ and again : “Petrol is their holy water and their creed is I believe in the gun almighty, the creator of heaven and earth.’” It goes on to ruminate on the bloodshed, the destruction, the waste of life and property: “What bales me”, he says, “is that it is all for the glory of God and the honour of Ireland.” ‘

The reviewer’s verdict was clear. He predicted that there would be queues to see it: ‘In topical flavour there are few plays in the repertory of the theatre to touch it. In satire it is in a class by itself- satire that bites, makes the bitten squirm, and onlookers laugh.’

For the Evening Herald, critic O’Donnell: ‘It was indeed a welcome and wholesome sign to sit in the Abbey Theatre and listen to an audience squirming with laughter and revelling boisterously in the satire, which Mr Sean O’Casey has put into his two-act play. It was brilliant, truthful, and decisive.’

The Freeman’s Journal reviewer, who admitted being ‘chilled’ at the prospect of a play with such a foreboding title, also considered it a success, strong in wit and characterisation. The play’s positive reception was similarly noted: ‘An appreciative audience with a bump of political cynicism, decided that Mr Casey’s play was a success and called him to tell him so.’ And Prior in The Irish Times predicted that it could have a long life, while suggesting that the ending might be emended so that it could play as a satire rather than a tragedy and concentrate on the strength of its characters: ‘From his bed, in which he lies for more than two thirds of the time, Seumus Shields fires off shot after shot of scornful denunciation of war and war -mongers. His stock seems to be quite inexhaustible; and though miserably frightened at every sign of physical danger, he is irrepressible.’

Joseph Holloway, chronicler of the theatre of the period, saw the play from the front seat of the stalls and wrote in his journal:

‘The scene was a room in a tenement in Dublin during the period of May 1920, and it proved a biting sarcastic study of many types of character during that stirring period of our history. The author, Seán O’Casey, set himself out to character sketch rather than to write a well-knit-together play. What it lacked in dramatic construction, it certainly pulled up in telling dialogue of the most topical and biting kind, and the audience revelled in its telling talk. Out of the crudeness of this first-acted play by the author, truth and human nature leaped and won the author a call at the end. During the second act, Mr W.B. Yeats sat a few seats away from me and applauded vigorously the play and the author.’

Program from Sean O’Casey’s ‘The Shadow of a Gunman’ which premiered at the Abbey. (Image: Abbey Theatre Twitter Account)

O’Casey had viewed the play from the wings on the first night but Lady Gregory, the Abbey Director, insisted he take one of the seats reserved for her and the poet and fellow director, W.B. Yeats, in the stalls on the following two nights (she and Yeats alternating in the other seat). The crowds turned up on the Friday night and by Saturday there were queues with many turned away. Holloway returned to see the play again and observed the author: ‘a thin-faced, sharp profiled man, with streaky hair, and wore a trench coat and a soft felt hat. He followed his play closely and laughed often, and I was told he was quite mannered almost to shyness and very interesting in his views.’

Lady Gregory brought O’Casey outside to see the crowds, which she believed were the largest since the Shaw play, The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet, had premiered. In conversation with O’Casey, he filled her in on his labouring background, his childhood, his reading, and the plays he had submitted previously to the Abbey. One was four years before, he told her. It was returned but marked: ‘Not far from being a good play.’ She continued in her diary: ‘He sent others and says how grateful he was to me because when we had to refuse the Labour one The Crimson in the Tricolour, I had said “I believe there is something in you” and “your strong point is your characterisation.” And I had wanted to pull that play together and put it on to give him some experience, but Yeats was down on it.’

The ’Labour’ play The Crimson in the Tricolour was first submitted by O’Casey to the Abbey on 6 January 1921. It was brought to the theatre by Micheál Ó Maoláin (Michael Mullins) who shared a room with O’Casey in Mountjoy Square. A native Irish speaker from the Aran Islands, Ó Maoláin had been a colleague of O’Casey in the Irish Citizen Army, set up to protect workers during the 1913 general strike, and was a clerk in the trade union headquarters, Liberty Hall. O’Casey was working as a caretaker for Delia Larkin’s workers’ club and involved on the side of her and her brother the labour leader, Jim Larkin, in the disputes within the union movement at that time. O’Casey was earning some money publishing songs and parodies and had written two pamphlets, a short history of the Irish Citizen Army and a memorial tribute to Thomas Ashe, who had died on hunger strike.

A founder member of the Citizen Army, he had helped write its constitution, but he had left the movement prior to the 1916 Rising in disagreements about the priority being given to the national struggle over the labour one (and in particular the election of Countess Markievicz to the army executive.) Having left the army, he wasn’t active in 1916 but did witness the impact of the battles in the city on the civilian population and was arrested on two occasions during the week.

O’Casey and Ó Maoláin had been sharing a room in the tenement at 35 Mountjoy Square since October of 1920 as O’Casey had left the family home. He found it intolerable to share with his brother Michael since his discharge from the British army at the end of the First World War and the recent deaths of their sister and mother. In a Radio Éireann documentary family members recalled them clashing over politics but also saw elements of ‘Mick’ in some of O’Casey’s characters. Ó Maoláin was interested in literature as well as politics and so he was an avid reader of any new work O’Casey produced.

The city was in turmoil that winter with regular raids from the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries as well as attacks and bombings by the IRA. Ó Maoláin estimated that the house was raided up to 18 times in that period as there was suspicion that IRA men on the run frequented the premises. A raid on Good Friday, 25 March 1921, began when the Black and Tans broke down the door of the house in search of two IRA men they believed to be in hiding there. According to Ó Maoláin, O’Casey was particularly frightened as he had in his possession a minute book of the Irish Citizen Army that if found would have certainly led to his arrest and worse. One of the occupants of the house, a father of a young family, was arrested on suspicion of aiding the escape of the IRA men. The following morning a group of Auxiliaries arrived to make a more thorough search and discovered bomb making equipment and ammunition in a carpenter’s shed at the back belonging to the landlord and his son. A mock firing squad was staged to frighten those arrested into giving more information and the house was locked down for a long period. During the gap between the two searches O’Casey had managed to remove the minute book to another location but the terror of the evening stayed with him and he left the building soon after, moving to another tenement building at 422 North Circular Road, where he had his own room to write.

The Crimson in the Tricolour had been read by Ó Maoláin as O’Casey was writing it in Mountjoy Square. He described it later as being ‘about the Nationalist movement and how Labour interacted with that movement that was there at the time. There was a very clever account of the lives of some of the well-off women who found out they had a country to save and who would be hurrying on to their men to take part in its management.’ O’Casey called it a ‘play of ideas’, moulded on Shaw’s style. One of his earliest extant pieces of written dialogue was a debate about Shaw’s work called The Crimson Corncrake. There a character defends Shaw against the accusation that he dealt with topics that nobody was interested in: ‘He treats of things which everyone OUGHT to be interested.’ The new play according to O’Casey had in it a ‘character posed on A(rthur) Griffith, a Labour leader, mean and despicable, posed on whomsoever you can guess.’ Two other characters, a ‘noble proletarian‘ and a carpenter, would be further developed in later works.

O’Casey had previously at least two short plays rejected by the Abbey, The Harvest Festival and The Frost in the Flower, but there had been some encouragement to persist and try again. This time there was no immediate rejection. Later in the summer of 1921 he discovered why. The text had been lost. Lennox Robinson, the Abbey Theatre manager and director, wrote to him on the June 13 asking if he had another copy of the text as he had mislaid it while moving house - ‘I had put away your play so carefully that I can’t find it’ - and he had not yet had it typed out. O’Casey replied that he had no copy and that ‘the task of rewriting it terrifies me but I suppose there is no other alternative.’ But in October Robinson wrote again to say he had found it while turning out some cupboards and hoped that O’Casey had not spent any time in trying to rewrite it.

Lady Gregory read the play, still hand-written, in November, and gave her report to Robinson: ‘This is a puzzling play - extremely interesting - Mrs Budrose is a jewel & her husband a good setting for her- I don’t see any plot in it, unless the Labour unrest culminating in the turning off of the lights at the meeting may be considered one. It is the expression of ideas that makes it interesting (besides feeling that the writer has something in him) & no doubt the point of interest to Dublin audiences - But we could not put it on while the Revolution is still unaccomplished - it might hasten the Labour attack on Sinn Féin, which ought to be kept back till the fight with England is over, & the new government has had time has had time to show what it can do.’

She made some editing suggestions and recommended that the play be typed for further review. Robinson sent on parts of her critique to O’Casey with her advice, saying that he himself liked ‘a great deal of it but thought some of it not necessary and not very good’ but offered to meet him to discuss the work on November 11th.

There were presumably some revisions of the play by O’Casey following that but it seems no further response as when summitting a new one act allegorical play, The Seamless Coat of Kathleen, in April, and saying he was working on a new play to be called On the Run, O’Casey asked again about the fate of Crimson. The play The Seamless Coat of Kathleen was based on the conflict between the pro and anti-Treaty sides at the Sinn Féin Ard-Fheis in the Mansion House in February 1922.

In reply Robinson said that while the directors liked the new work, they thought it ‘too definite a piece of propaganda’ to put on. However, Robinson said that he would go over The Crimson in the Tricolour again and on this occasion the play was sent to W.B. Yeats for comment. Yeats was more dismissive:‘I find this discursive play very hard to judge for it is the type of play I do not understand. The drama of it is loose and vague…It is a story without meaning- a story where nothing happens except a wife runs away from a husband, to whom we had not the least idea that she was married & the Mansion House lights are turned out because of some wrong to a man who never appears in the play. On the other hand it is so constructed that in every scene there is something for pit and stalls to cheer or boo. In fact it is the old Irish idea of a good play -Queens Melodrama brought up to date would no doubt make a sensation - especially as everybody is as ill-mannered as possible, & all truth considered as inseparable from spite and hatred. If Robinson wants to produce it let him do so by all means & be damned to him. My fashion has gone out.’

Robinson sent some of these comments on to O’Casey, without attributing them to Yeats, (though O’Casey did find out) saying that while he agreed with some of the criticism, he did find it interesting and if O’Casey was still interested in the subject he would help him with it or alternatively look at something else from him. O’Casey took this as a rejection: ‘I am terribly disappointed at its final rejection, and felt at first as if, like Lucifer, I had fallen never to hope again. I have re-read the work and find it as interesting as ever, in no way deserving of the contemptuous dismissal it has received from the reader you quoted.’He then went on to take issue with some of the criticism, citing the example of Ibsen and Shaw in his defence and even used Yeats’ political activity as a precedent. He quoted the reader as saying of one of the characters: ‘Regan talks constantly of his contempt for organised opinion, and suddenly we discover him some kind of labour leader - one organised opinion exchanged for another.’ To which criticism O’Casey replied:

‘Well, what then? Every thinker has a contempt - more or less - for organised opinion; but he may have a decided regard for organised action. I know Republican philosophers who have a supreme contempt for the organised opinion of the Free State, but who have, when bullets are flying about, a wholesome regard for that opinion in action. Besides it has often happened that a thinker suddenly leaves his solitude to oppose a general or particular act of injustice. Voltaire did so, and Zola, W.B. Yeats and “AE” did so in 1913 during the strike.’

He thanked Robinson for his invitation to discuss his work and informed him he was

‘... engaged in the writing on a play at present - On the Run - the draft of the first act is finished and most of the second. Would it be well to wait until this is completed and then make the bringing of the work to you an opportunity of having a talk with you? It deals with the difficulties of a poet who is in continual conflict with the disturbances of a tenement house, and is built on a frame of Shelley’s phrase: “Ah me, alas, pain, pain ever, forever”.’

On 17 November 1922, O’Casey wrote to Robinson to say the play was ready, and typed (he had purchased a typewriter after his move to North Circular Road)! Robinson gave the play first to Yeats this time and on 25 February 1923, he wrote to confirm its acceptance: ‘I am very glad to say that Mr. Yeats likes your play On the Run very much and we will try and put it on before the end of our season. Lady Gregory hasn’t read it yet but I am sure her opinion of the play will be the same as Mr. Yeats. The play will need a little cutting here and there. I like it very much myself.’ Underlining his commitment to the work he subsequently decided to direct it himself. The title had to change as they were aware of another play with the title On the Run. The new title came from the words of Donal Davoren, the poet who kept quoting Shelley, at the end of Act One: ‘A gunman on the run! Be careful, be careful Donal Davoren. But Minnie is attracted to the idea, and I am attracted to Minnie. And what danger can there be in being the shadow of a gunman?’ The play was now and forever The Shadow of a Gunman.

In a manuscript note O’Casey had written ‘Mullen as a character in a play’ and this became Seumas Shields, a pedlar, who was the tenant in the tenement in Hilljoy Square where the play is set. The play begins with Shields being given notice to quit by his landlord and captures the poverty, humanity and humour of tenement life as well as the terror that is outside: a terror that is soon realised as the raid by the Black and Tans that O’Casey and Ó Maoláin experienced the previous Easter is revisited with a tragic coda. Shields carries most of the edge and humour of the play and is sharp in his assessment of the current state of the country.

Davoren: I remember the time when you yourself believed in nothin’ but the gun.

Seumas: Ay, when there wasn’t a gun in the country. I’ve a different opinion now there’s nothing but guns in the country….. It’s the civilians that suffer; when there’s an ambush they don’t know where to run. Shot in the back to save the British Empire, an’ shot in the breast to save the soul of Ireland…

I’m a Nationalist right enough; I believe in the freedom of Ireland, an’ that England has no right to be here, but I draw the line when I hear the gunmen blowin’ about dyin’ for the people when it’s the people that are dyin’ for the gunmen!The play ends with the death of Minnie who has been arrested when a package she was hiding on behalf of the ‘shadow gunman’ turned out to be real ammunition. Arrested and brought away by the Auxiliaries, she is shot ‘in the buzzom’ when their lorry is attacked by the IRA, so a ‘friendly’ fire causality of war.

And Davoren ends with his Shelly lament:

‘“Pain, pain, pain ever, for ever” It’s terrible to think that little Minnie is dead, but it’s still more terrible to think that Davoren and Shields are alive! Oh, Donal Davoren, shame is your portion now till the silver cord is loosened and the golden bowl be broken. Oh, Davoren, Donal Davoren, poet and poltroon, poltroon and poet!

Seumas (solemnly): I knew something ud come of the tappin’ on the wall!’The success of those first nights of Gunman saw O’Casey fully embraced into the Abbey community. He had an open invitation to attend any play. He attended rehearsals and engaged with the Abbey actors about their work and his texts. Lennox Robinson gave him a copy of Chekhov’s plays, invited him to dinner at his club and afterwards to visit W. B. Yeats in his new home on Merrion Square. It was a big change for O’Casey who had failed to recognise Yeats at the opening night of Gunman when he was put into a seat beside him. Soon he would be attending a special performance of a Yeats play in the author’s home and later receive the ultimate accolade of an invitation from Lady Gregory to stay at Coole Park.

In engaging with the Abbey actors, O’Casey returned to his rejected play The Crimson in the Flag. He brought it to the actor, Michael J. Dolan, who had played the part of Tommy Owens in Gunman to get his advice on the manuscript. Joseph Holloway witnessed the consultation and had his first long discussion with O’Casey who told him of his plan to one day write a play called the Orange Lily ‘in which he would depict the feelings of a good type of Orangeman who wished well of Ireland, leading up to Easter Week 1916.’

O’Casey sent a revised version of the play together with the critical comments of Yeats to Dolan some days later. He offered to show him and two other actors who he wished to read the play, the more positive comments of Lady Gregory which might influence any further redrafting suggestions.

Dolan did read the play for F. J. McCormick (Seumas Shields in the play) and Arthur Shields (Donal Davoren) but however all were agreed that it was not a ‘good proposition for the stage’ and to put it on would mean ‘undoing your good work of the Gunman.’ But he did offer to discuss it further and later passed on a new version of the play to Robinson.

Dolan told Holloway about the draft: ‘It was impossible. The first scene was outside a convent with people spouting socialism for no earthly reason.’ Dolan suggested if he wanted his characters to spout such stuff, the bar of a pub would be a more likely setting. O’Casey had acted on his suggestions and made one of the scenes take place in a pub… O’Casey takes kindly to advice.’

Robinson was to reject the play again, supported by Lady Gregory, who wrote to Robinson after reading the play with Jack B. Yeats in Coole. He considered it ‘a topical play that has missed its point’ she told Robinson.

The Abbey did accept one of two other short plays that O’Casey submitted that summer, a reworked version of The Seamless Coat of Kathleen called Kathleen Listens In. O’Casey considered the other work, The Cooing of the Doves, to be the better work and it may have incorporated some of Dolan’s suggestions for Crimson as according to O’Casey it consisted of arguments and debates set in a public house. Kathleen, however, was not a success when the Abbey presented it in October.

The Shadow of A Gunman returned to open the new Abbey season in August 1923 to large houses and much acclaim. Holloway’s conversations with O’Casey were, by now, a regular feature of his diary and on September 10th he recalled their conversation of the previous evening after a performance of Yeats’ Cathleen ni Houlihan: ‘He told me he had been raided several times lately. Last week he had been awakened out of his sleep with hands pulling the sheet off him, and a light full in his eyes, and three revolvers pointed out. He was hauled out of bed and roughly handled, as they queried his name etc. He knew of a fellow, a member of the IRA, who was on the run, being taken in the middle of the night by the CID men and brought out toward Finglas and brutally beaten with the butt end of their revolvers, and then told to run for his life while they fired revolver shots after him, taking bits off his ears etc and catching up on him again renewed their beating. Next day O’Casey saw the chap and could hardly recognise him, so battered and bruised was he. Such brutality demoralises a country.’

O’Casey later identified the victim as a Captain Hogan, a boyfriend of Mary Moore, one of the family that lived above him on North Circular Road. Hogan had been captured at the Dorset Street end of North Circular Road and found dead on a ‘lonely Finglas Road’. He was Martin Hogan originally from Clonmel, County Tipperary, whose ‘bullet riddled’ body was found in a ditch on Greenpark Road, Drumcondra on 21 April 1921. During the follow-up search of the North Circular Road house a number of the Moore family were arrested, including the daughter Mary, and it was to have a traumatic effect on the mother of the family who died shortly after. These events were to be the basis of the opening line of his next play when the character Mary Boyle reads from the newspaper: ‘On a little by-road out beyant Finglas, he was found.’

Another Abbey actor, Gabriel Fallon, recalled that O’Casey had been talking of basing a play on the death of a crippled IRA man called Johnny Boyle. In Autobiographies, O’Casey dates Boyle’s injury to a battle in O’Connell Street following the occupation of the Four Courts at the start of the Civil War. O’Casey had told Robinson during the Gunman rehearsals that all his characters came from real life though he need not worry about them recognising themselves in a prediction that proved not to be true as a real life model for the ‘Captain’ in the next play threatened to sue.

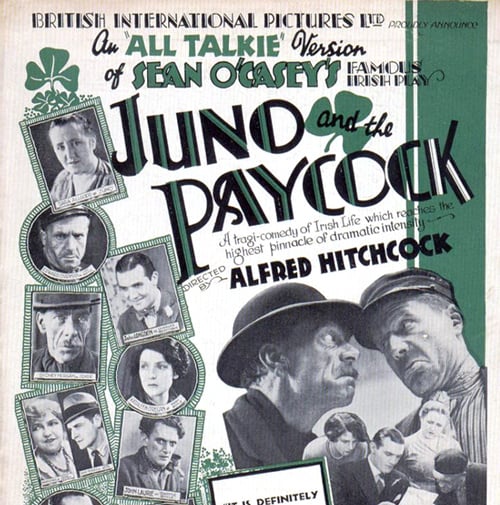

The play was submitted by O’Casey to Robinson on December 28th and accepted. When the notice of the play was put up for the actors, Fallon saw that it was to be called: Juno and the Paycock.

An earlier manuscript of the play is in the O’Casey papers in the National Library of Ireland. It is in a Grattan school copy book which also had a clipping from The Irish Times showing when the work began. In the notebook are outlines of the action of the first two acts with:‘ Act 1- Annie on strike: mother going out to work. Joxer enters when Juno leaves: enters singing. His talk with Andy interrupted. The dispute between the two of them. The lover of Annie’s. The entrance of the schoolteacher. The writing of the will.’

As with Gunman the economic context of the tenement is clearly set from the beginning. There are drafts of snatches of dialogue, lists of the characters in the play on another page and even a sketch of the ‘Captain’. But the bulk of the notebook is a full draft of two Acts. The opening scene with the newspaper and the news of the shooting is not yet there as the play begins with Mrs B and Mary and their talk of Johnny offering up’ a novena to get a job.’. But all the elements of the play are there almost fully formed. The crackling dialogue between Joxer and ‘Captain’ Boyle, the plot which tangles the challenges of poverty, civil war and betrayal and the towering humanity of the women characters, Juno, Mary Boyle and Mrs Tancred. The most memorable lines of the play are sketched out in this early draft: ‘cold and watery light looked up at the stars & and I assed myself the question – What is the stars?’; Joxer: ‘A darlin word ... a darlin word’; and a phrase that would eventually end a third Act of the play: “’I’m telling you Joxer, the whole world is in a state of chassis.’ There too is Mrs Tancred’s lament for the death of her son and the son of her neighbour in an ambush in the mountains: And now here’s the two of us, oul women standin’ one on each side of the scales o’ sorra, balanced by the bodies of our two dead children. Mother O’, mother o God have pity on the pair of us! Oh blessed divine Queen of Heaven where were you when me darlin son was riddled with bullets? Sacred Heart of the Lovin Crucified Jesus, take away our hearts o stone & give us hearts of flesh; take away this murderin hate ... aan’ give us thine own Eternal love!”

(In this draft the body was found near Coolock, Finglas was the location in the final version.)The echo of these words by Juno is yet to come.

When the cast assembled to rehearse the play at the end of February 1924 it was the strongest the Abbey could produce. Sara Allgood, who had made her name in Synge’s plays, was Juno, F.J. McCormick was Joxer Daly, Barry Fitzgerald was Captain Boyle and Eileen Crowe was Mary Boyle. Michael. J. Dolan who had recently become the theatre manager was the director and also played a small role. Gabriel Fallon, who played Mr. Bentham recalled that the rehearsals were tentative and that they were unsure of the quality of the work. O’Casey was present for some and there were alterations to the text in performance (an off stage execution of Johnny Boyle was removed).But Fallon’s view changed when he witnessed the dress rehearsal and particularly the two final Acts which together with the comedy of Joxer and the Captain found Juno facing her own tragedy. Fallon recalled watching the play just behind the author at the rehearsal and his realisation that he was watching the work of a ‘genius’…”with an ensnaring slow impetus of a ninth great wave (Sara) Allgood’s tragic genius rose to an unforgettable climax and drowned the stage in sorrow. Here surely was the very butt and sea mark of tragedy! But suddenly the curtain rises again: are Fitzgerald and McCormick fooling, letting off steam after the strain of rehearsal? Nothing of the kind; for we in the stalls are suddenly made to freeze in our seats as a note beyond tragedy, a blistering flannel-mouthed irony sears its maudlin way across the stage and slowly drops an exhausted curtain on a world disintegrating in “chassis”.’

A poster for Alfred Hitchcock's screen adaptation of Sean O'Casey’s Juno and the Paycock, released in 1930 (Image: Filmaffinity)

When the play opened on March 3rd, the audience had the same reaction. Joseph Holloway was there: ‘The last act is intensely tragic and heart-rendingly real to those who passed through the terrible period of 1922...the tremendous tragedy of Act III swept all before it, and made the doings on the stage real and thrillingly in their intensity.’ The crowds had to be turned away for the rest of the run. Lady Gregory was there with Yeats on March 8th, writing in her diary: ‘A wonderful and terrible play of futility, of irony, humour, tragedy.’ When she met O’Casey he again talked of the rejection of Crimson: ‘You were right not to put it on, I can’t read it myself now. But I will tell you that it was a bitter disappointment for I not only thought that it was the best thing that I had written, but I thought that no one in the world had every written anything so fine…I owe a great deal to you, Mr. Yeats and Mr. Robinson, but to you above all. You gave me encouragement. And it was you who said to me upstairs in the office... “Mr O’Casey your gift is characterisation.” And so I threw over my theories and worked at characters, and this is the result.’

Lady Gregory wrote that Yeats thought it ‘very fine, reminding him of Tolstoy. He said when he talked of that imperfect first play “Casey was bad in writing of the vices of the rich which he knows nothing about but he thoroughly understands the vices of the poor.”‘ Her own verdict was emphatic: ‘But that full house, the packed pit and gallery, the fine play, the call of the mother for the putting away of hatred- “give us Thine own eternal love!” made me say to Yeats “This is one of the evenings at the Abbey that it makes me glad to have been born.’ She returned the following day. The house was so packed she had difficulty finding seats for Jack Yeats and his wife. She watched the play with O’Casey expressing how moved she was by the mother’s plea. He would travel to Coole and their bond would become closer as they talked of their own mothers’ love. O’Casey was to call the chapter about her in his autobiography ‘Blessed Bridget O’Coole’.

But her journal entry for that day, 9 March 1924, ends with a reminder that shadows were still around: ‘This morning’s papers tell of the revolt of the officers.’ The army ‘mutiny’ added to the tension of the play the following week.

O’Casey was now a central part of the Abbey community and Holloway’s diary for the following months has a number of accounts of their discussions after plays at the theatre. They discussed plays, actors and authors, Shaw in particular, but also politics, the terror and the ‘savagery‘ O’Casey had witnessed, that inspired his work and the terror that was still happening in the country. On 20 May 1924 they met in Webb’s bookstore where O’Casey had bought a volume of AE’s collected poems. Holloway wrote in his journal: ‘I mentioned that he would be writing his next play amongst the stars. Then he told me of the play with the title The Plough Amongst the Stars he had in mind to write.’

O’Casey had not forgotten the theme of Labour and the Nationalist movement that was The Crimson in the Tricolour nor his experience wandering in the ruins of the Easter Rising. He had learned a lot from the criticism of the early play: The recommendation by Lady Gregory to focus on character; the suggestion from Dolan to put debates into a pub setting as he had done with the redraft of Crimson and the rejected Cooing of the Doves. From those embers he fashioned the second Act of this new work, set in pub as the Citizen Army and the Irish Volunteers are addressed stirringly outside. From Crimson he revived the two of most vivid characters, Fluther, the carpenter and The Young Covey, the ‘noble proletarian’. The early play had served its purpose and was not of any further use. It was to be lost again, mislaid amongst Lennox Robinson’s papers and not found by Robinson or his executors when O’Casey sought it out.

When The Plough and the Stars was finished and submitted on 12 August 1925, it would complete Seán O’Casey’s trilogy on the Irish Revolution. The Plough’s second Act, with Fluther, The Young Covey and Rosie Redmond and the unfurling of the tricolour in the public house would lead to protests and a riot prompting the poet and Nobel Laureate, Yeats to declare from the stage: ‘You have disgraced yourselves again!’

Seán O’Casey’s mother, in trying to discourage his activism, had told him: ’You’ve done enough for Ireland, Jack!’ The work of these years was to be his lasting legacy. The blood on the flag was now in sharp sunlight, the shadows exposed to show the city and its people in all their pain and glory.

No. 422 North Circular Road, the house where Seán O’Casey wrote his acclaimed trilogy of plays, 'The Shadow of a Gunman' (1923), 'Juno and the Paycock' (1924) and 'The Plough and the Stars' (1926). The property was purchased by Dublin City Council in 2020. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Further Reading

Seán O’Casey, Three Plays (London

1980)

Seán O’Casey,

Autobiographies 1 and 2 (London, 1992)

Seán O’Casey,

The Dublin Trilogy: A Casebook, edited by Ronald

Ayling (London 1985)

Christopher Murray,

Seán O’Casey Writer at Work (Dublin,

2006)

Garry O’Connor,

Seán O’Casey A Life (London, 1988)

The Letters of Sean O’Casey, 4 Volumes, edited

by David Krause, New York, 1975, 1980 (Washington 1989,

1992)

Seán O’Casey,

Feathers from the Green Crow, edited by Robert Hogan

(London,1963)

Seán O’Casey, The Harvest Festival

(Gerrard’s Cross, 1980)

Lady Gregory, The Journals, Volume 1, edited by

Daniel J. Murphy (Gerrard’s Cross, 1978)

Joseph Holloway’s Irish Theatre, edited by

Robert Hogan and Michael J. O’Neill (Southern Illinois,

1967)

David Krause,

Seán O’Casey:The Man and His Work (New

York, 1975)

Gabriel Fallon,

Seán O’Casey: The Man I Knew (London,

1965)

Lennox Robinson,

Curtain Up: An Autobiography (London, 1942)

Robert Hogan and Richard Burnham,

The Modern Irish Drama: A Documentary History VI: The Years

of O’Casey 1921-1926 (Gerrards Cross, 1992)

Christopher Murray,

A Faber Critical Guide: Seán O’Casey

(London, 2000)

C. Desmond Graves, Seán O’Casey: Politics and Art

(London, 1979)

The World of Seán O’Casey, edited by

Sean McCann (London, 1966)

Bernice Schrank,

Seán O’Casey; A Research and Production

Sourcebook (London, 1996)

Saros Cowasjee,

Seán O’Casey: The Man Behind the Plays (London, 1963)

Colm Tóibín,

Lady Gregory’s Toothbrush (Dublin, 2002)

Elizabeth Coxhead,

Lady Gregory: A Literary Portrait (London, 1966)

The O’Casey Enigma, Edited by Micheál

Ó hAodha (Dublin 1980)

The Abbey Theatre: Interviews and Recollections,

edited by E. H. Mikhail, (London, 1988)

Essays on Seán O’Casey’s

Autobiographies, edited by Robert G. Lowery (1983)

Victoria Stewart,

About O’Casey: The Playwright and the Work

(London, 2003)

Hugh Hunt, The Abbey Theatre (Dublin 1979)

Charles Townshend, The Republic (London, 2014)

Michael Laffan, Judging W.T. Cosgrave (Dublin,

2014)

Dorothy Macardle, The Irish Republic (1968)

Diarmaid Ferriter,

Between Two Hells, The Irish Civil War (London,

2021)

Please click here to read the fully annotated PDF version of this article.