Attempted transatlantic flights end in failure and mystery

Clifden, 21 May 1919 - The whereabouts of Australian aviator Harry Hawker and his navigator Kenneth MacKenzie Grieve remains a mystery, after their unsuccessful attempt to complete the first transatlantic flight.

They set off from St John’s in Newfoundland, Canada at 6.48 pm on Sunday 18 May in Hawker’s Sopwith aircraft and were expected to reach the Irish coast at around 3 pm the following afternoon but never arrived. The airmen are well supplied with provisions so it is believed that if they made a safe landing in the water they have a good chance of keeping themselves afloat for two or three days in the hope of being picked up by a passing ship.

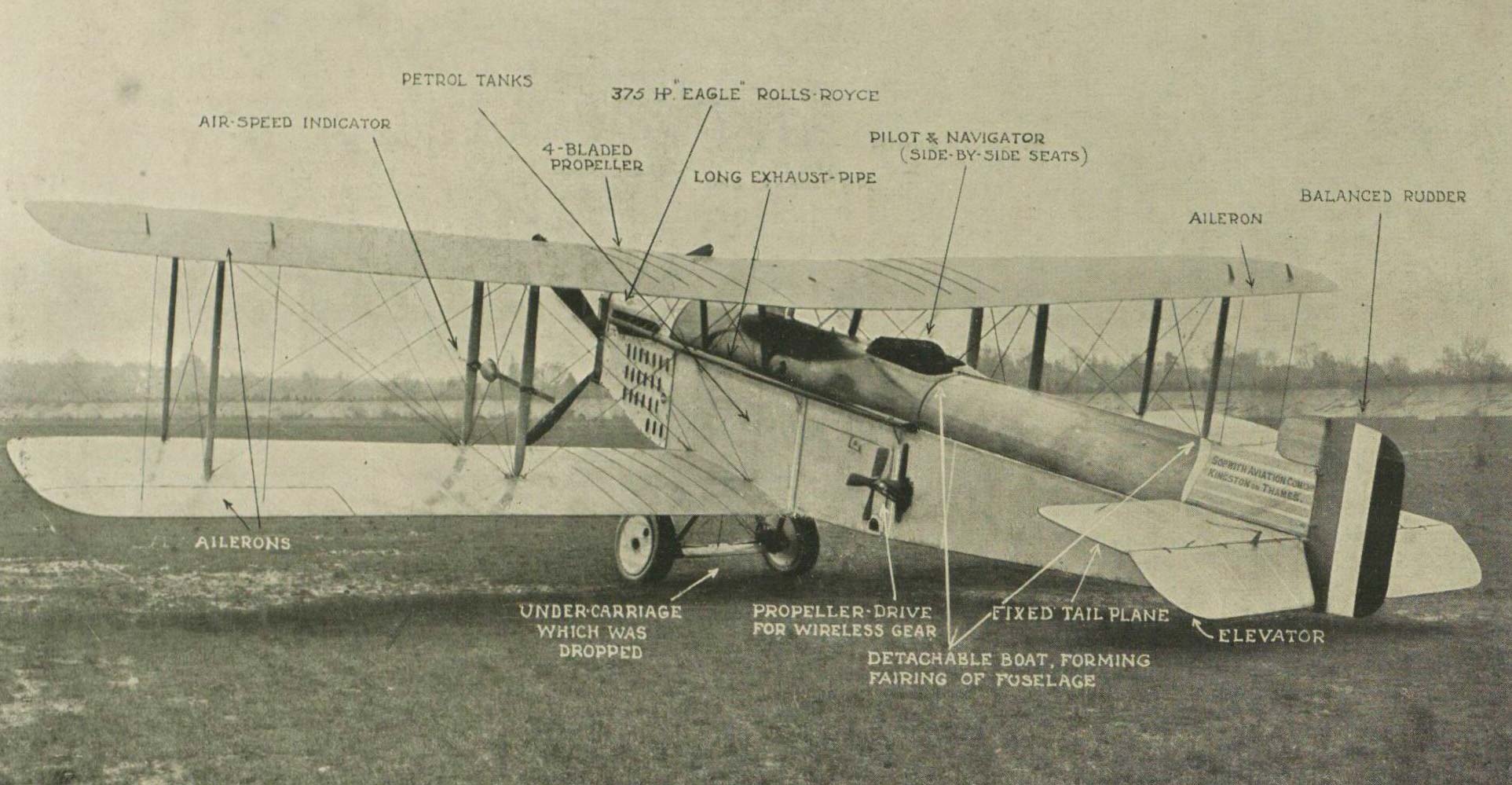

A more detailed look at Hawker's machine. Note the detachable lifeboat to the rear of the area where the pilot and navigator sit (Image: Illustrated London News, 24 May 1919)

Hawker’s history

This is not Hawker’s first entry in a high profile aerial

race. In August 1913, he attempted to claim a £5,000 prize

offered by the Daily Mail for a waterplane flight around

Great Britain. On that occasion, however, his efforts came unstuck

over Ireland and he was forced into a descent at Loughshinny near

Skerries.

Despite failing to complete the course in 1913, the directors of the Daily Mail saw fit to to pay Mr Hawker £1,000 on account of his effort and the paper has once again paid him tribute. ‘It was literally Mr Hawker alone against the United States. On one side there was a man, on the other the whole organisation of a great Navy and State. While 60 American warships were told off to patrol the American route, Mr Hawker was left to himself… Nothing can dim the splendour of his attempt or detract from the will-power, courage, and national enthusiasm which have inspired it.’

Other attempts

Hawker and Grieve are not alone in attempting the hazardousness of

the transatlantic undertaking. They are part of

a great race, with a £10,000 prize offered by the Daily Mail,

to make history and be the first to fly non-stop across the

Atlantic Ocean.

An earlier attempt, made by Englishman Major Woods, failed before it began, his aircraft crashing in the Irish Sea on the way to his starting point in Limerick.

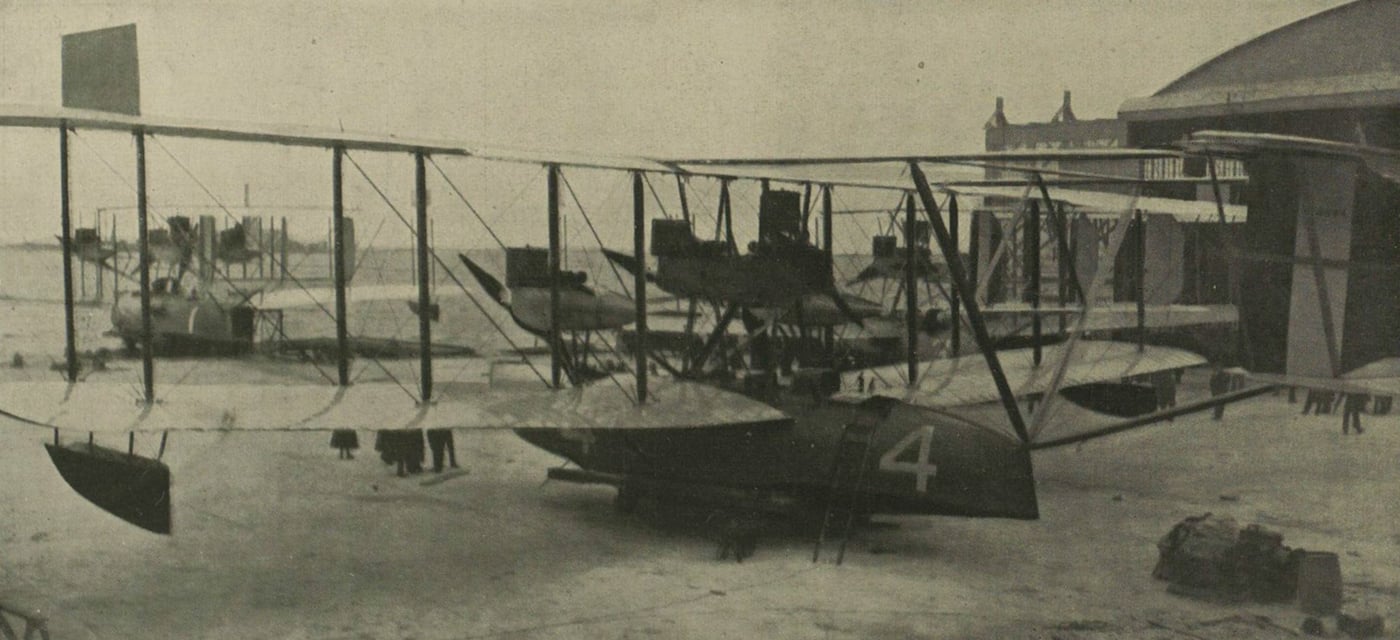

Also taking on the challenge were three American seaplanes, which left from Trepassy Bay, Newfoundland, on 16 May. They flew close together for a considerable distance after their take-off until they reached within 200 miles of Corvo Island, where they encountered fog.

One of the US seaplanes, the NC4, arrived at Horta in the Azores the day after it departed from Trepassy and its pilot, Lieutenant Commander Read, has communicated by telegram that he and his crew were all fit and fine, but tired.

The NC3 trailed the NC4 by 30 minutes just before the approach to Azores and it appears to have lost its way in the fog. The NC1 also went off course and the crew were forced to alight in the open sea 200 miles northwest of Faval. Four destroyers and some steamships went to their assistance.

|

|

Top: The crew of the NC-4 which successfully reached the Azores. Bottom: The naval seaplanes with the NC-4 in the foreground. (Images: Illustrated London News, 24 May 1919)

The future of flight

Beyond the stories of individual daring, the race across the

Atlantic has highlighted the rapid advances in flight.

As the Irish Times has observed, it is only 12 years or so since Alberto Santos Dumont made the ‘first authentic flight in an aeroplane’ in Europe when, in November 1906, he flew a mere 230 yards. Less than three years later, in July 1909, Louis Blériot flew over the Straits of Dover.

What is being attempted now is a distance of nearly 1,900 miles, the speed of progress leading the Irish Times to imagine a future where Atlantic flights become as common as cross-Channel sailings.

[Editor's note: This is an article from Century Ireland, a fortnightly online newspaper, written from the perspective of a journalist 100 years ago, based on news reports of the time.]