American political culture, Ireland and the League of Nations

By Prof. Robert Schmuhl

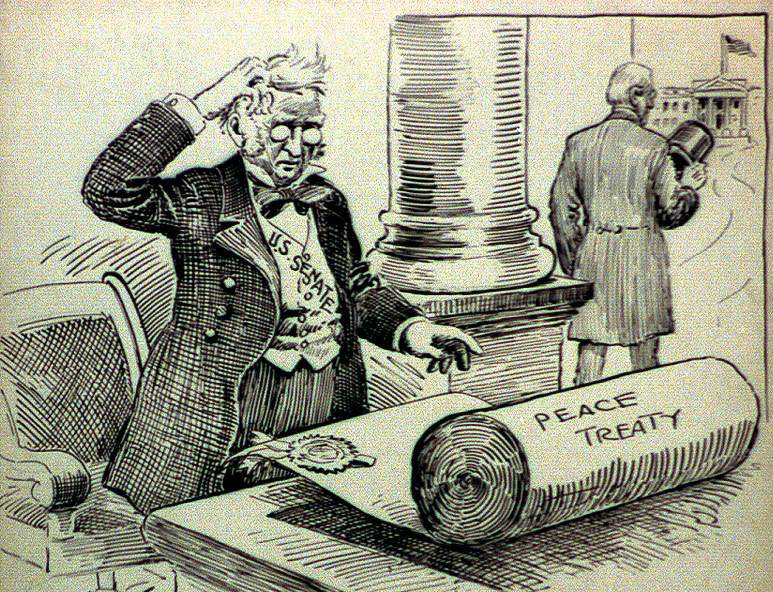

When the United States Senate failed to ratify the Treaty of Versailles on 19 November 1919, President Woodrow Wilson suffered much more than the defeat of a major policy initiative he was instrumental in formulating. The Senate vote, the first time a peace treaty was ever rejected and primarily a consequence of idealistic obstinacy and Irish-American pressure, helped return the Republican Party to the dominant position in American politics, a place it occupied until Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Democrats swept to victory in 1932.

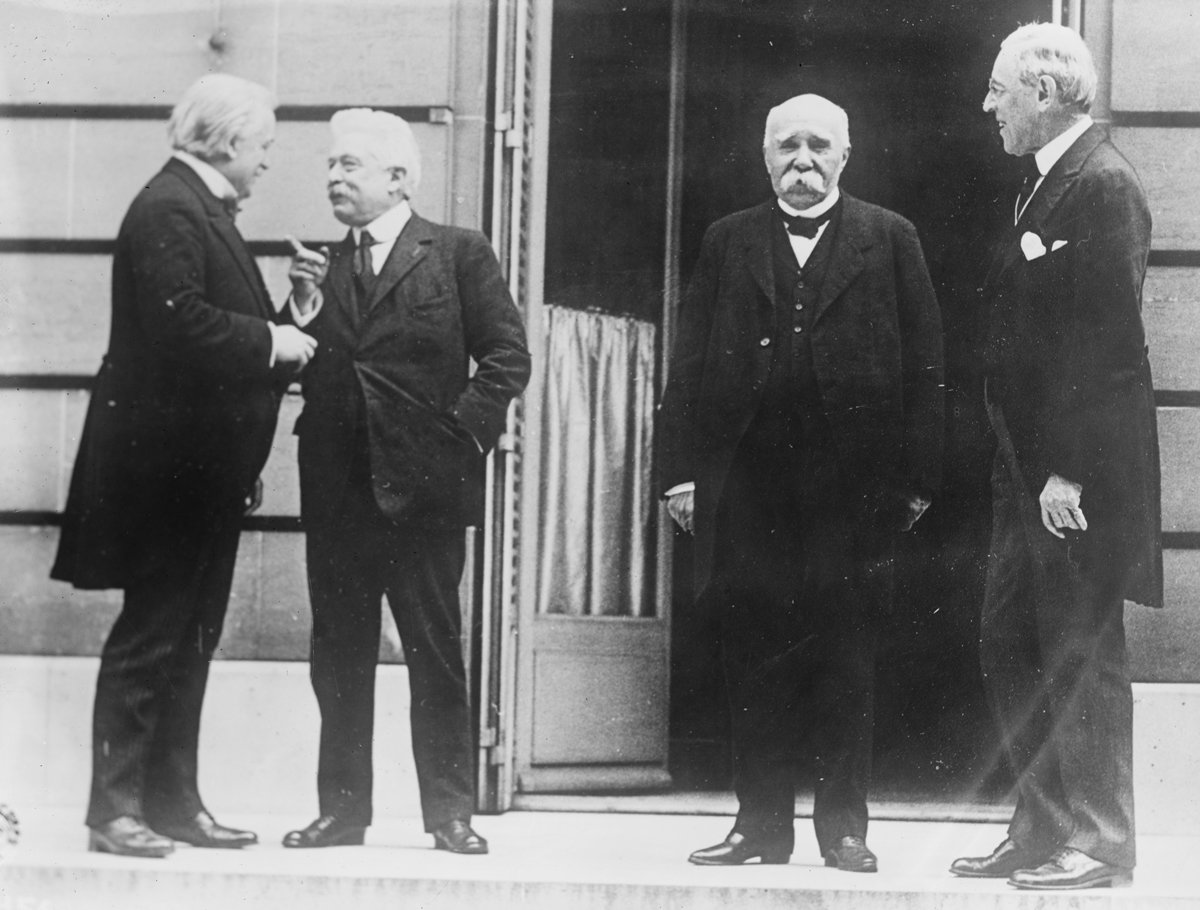

A hundred years later, 1919 is one of the most atypical, indeed strangest, years in the history of the American presidency. Serving his second term after winning a close re-election in 1916, Wilson spent all but three weeks of the first half of 1919 abroad—in Paris at the Peace Conference following the Armistice of the Great War. The first sitting president to travel to Europe, Wilson (with the length of his stay and his personal involvement in the meetings) dramatised that the United States wanted a commanding role on the world stage. The noted English writer H.G. Wells captured the public’s opinion of Wilson in trying to solve the post-war puzzles for a peaceful future. ‘He was transfigured in the eyes of men. He ceased to be a common statesman; he became a Messiah,’ Wells observed; ‘millions believed him as the bringer of untold blessings; thousands would gladly have died for him’.

Messianic parallels aside, the president had come a long way from his days as a professor, university president, or governor. The Treaty of Versailles, with its covenant establishing the League of Nations, was signed in France on 28 June 1919, and Wilson returned to the U.S. on 8 July to a ticker-tape parade in New York City and to the cheers of an estimated 100,000 people at Union Station in Washington, D.C.

The 'big four'. Left to right: Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Premier Vittorio Orlando, Premier Georges Clemenceau, and President Woodrow Wilson at the Peace Conference in Paris, 27 May 1919.

Heady, even intoxicating experiences can alter one’s thinking, and over the course of the next several weeks Wilson seemed to forget some lessons about the significance of democratic comprise he used to lecture about in collegiate classrooms. The president took charge of persuading the Senate to approve the treaty. According to the U.S. Constitution, two-thirds of senators are required to vote for its ratification, and in 1919 that meant a total of 63 ‘yeas’ supporting the treaty, if the entire chamber was present. At the time, Republicans held a slim majority of 49 seats to the Democrats’ 47, meaning that Wilson needed at least 16 Republican senators to back the treaty.

Taking matters in his own hands, Wilson carried the treaty to Capitol Hill on 10 July, delivering a nearly forty-minute address to the Senate. ‘Dare we reject it and break the heart of the world?’ he asked at one point. His own response assumed a spiritual, almost mystical tone: ‘the stage is set, the destiny disclosed. It has come about by no plan of our conceiving, but by the hand of God who led us this way. We cannot turn back. We can only go forward, with lifted eyes and a freshened spirit, to follow the vision. It was of this that we dreamed at our birth. America shall show the way.’

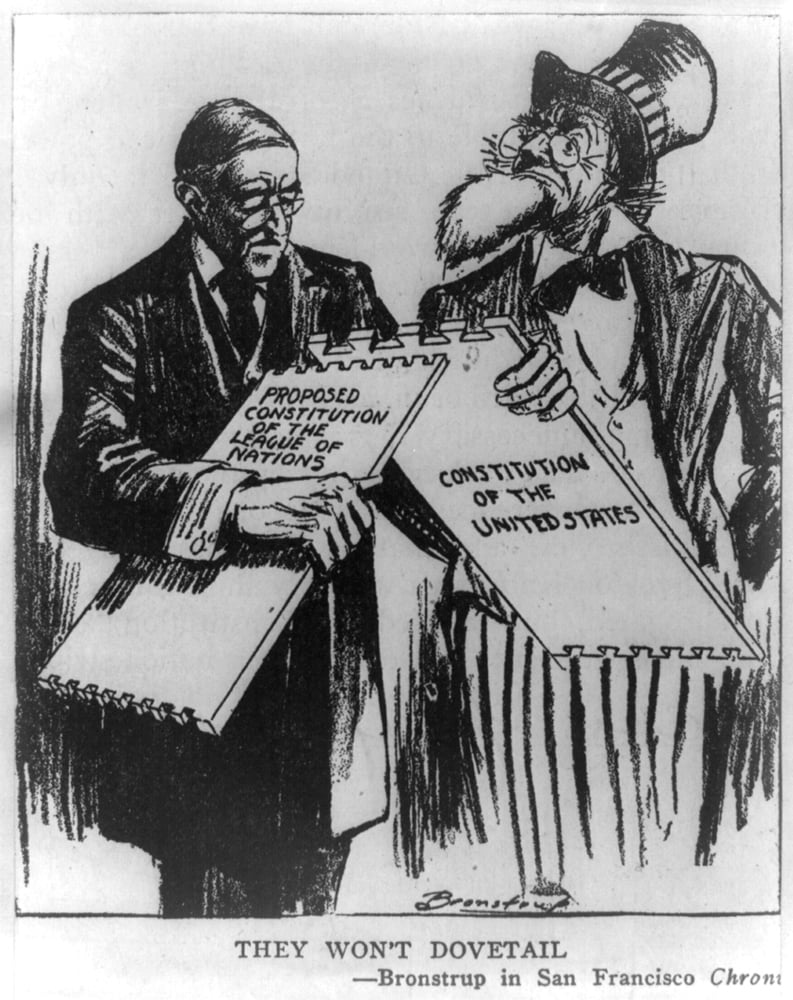

At the end of that month, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee began six weeks of deliberations on the treaty and its specific elements. On 19 August in a departure from Congressional tradition, Wilson personally made his case to the committee. He defended the document’s provisions, including the controversial Article X, which said that a member of the League of Nations was expected to assist another member in the event of an outside threat. The exact language, in part, states: ‘the Members of the League undertake to respect and preserve as against external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all Members of the League.’

Several senators worried that Article X would limit American independence and even sacrifice the nation’s sovereignty. The Chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts spoke for more than himself when he told Senate colleagues: ‘I have never had but one allegiance—I cannot divide it now. I have loved but one flag and I cannot share that devotion and give affection to the mongrel banner invented for a league.’ Some Republican senators, dubbed the ‘Irreconciliables’, were unalterably opposed to the treaty and to the league. A larger group, referred to as ‘Mild Reservationists’, sought textual changes before delivering a final verdict—or vote—on the entire treaty.

Wilson, however, rejected all proposals for modification and refused to compromise with senators in the opposing party. The treaty that his idealism helped inspire and brought into being over in Paris would stay in the exact form he’d signed at Versailles. Reservationists of whatever degree had no role to play, as far as the president was concerned. He thought he knew better, and he planned to achieve Senate ratification by trying a new, people-oriented approach.

On 3 September, Wilson set off from Washington on a speaking tour by train to rally support for the League of Nations—and Senate approval of the whole treaty. Covering 8,000 miles during twenty-two days, the president made speech after speech in an attempt to provoke the public to bring pressure on their senators to support ratification. He argued his position from the highest of plains, concluding remarks in Portland, Oregon, on 15 September:

‘I am glad for one to have lived to see this day. I have lived to see a day in which, after saturating myself most of my life in the history and traditions of America, I seem suddenly to see the culmination of American hope and history—all the orators seeing their dreams realised, if their spirits are looking on; all the men who spoke the noblest sentiments of America heartened with the sight of a great nation responding to and acting upon those dreams, and saying, “At last, the world knows America as the savior of the world!”’

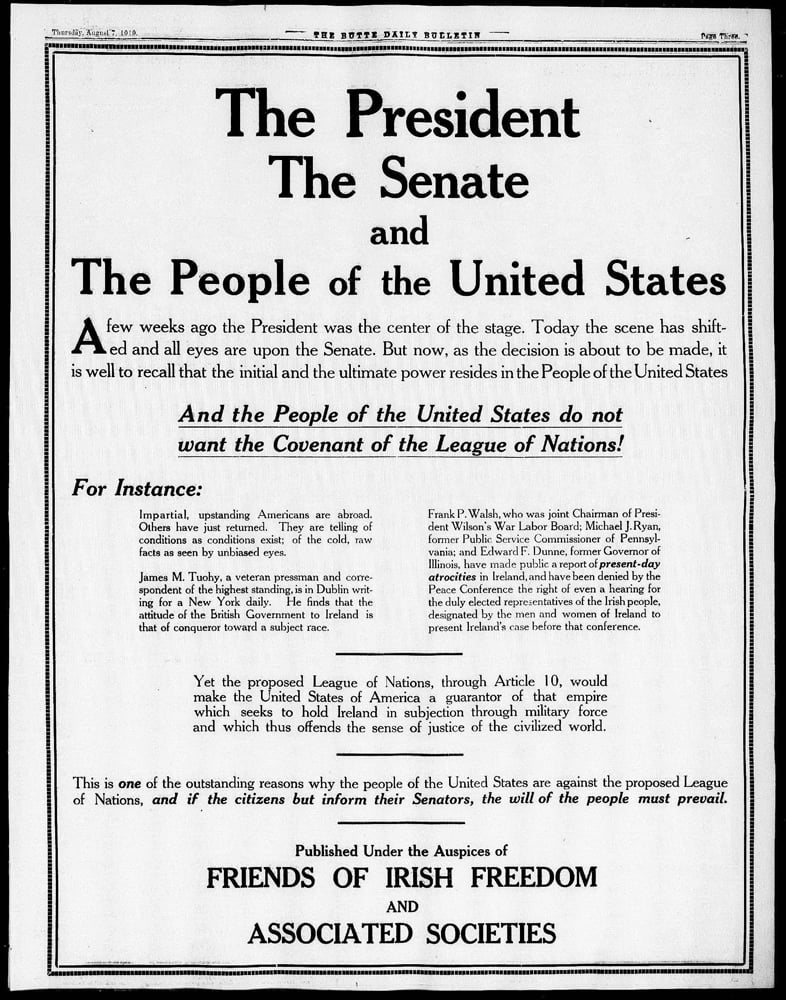

At the same time Wilson was drawing large crowds to his appearances, so, too was Éamon de Valera, who had arrived as a stowaway in New York a month before the president’s return from Europe. De Valera, at the time prime or chief minister of Dáil Éireann, was introduced to American audiences as the ‘President of the Republic of Ireland’, and he had come to the States to build support for Irish independence, to advance the establishment of an Irish republic in Washington, and to raise money for his cause. Given that Wilson made national self-determination a central tenet of his world view, the Irish in both Ireland and the U.S. kept pushing him to take a stand on their behalf, something he refused to do.

Despite long-standing allegiance to the Democratic Party, especially in urban areas, the American Irish turned on Wilson and his effort to sell the treaty. As the president arrived in a city, local newspapers carried advertisements, sponsored by the Friends of Irish Freedom, opposing Wilson and the League of Nations he was championing. In addition, pamphlets circulated that charged Wilson with hypocrisy for not recognising the cause of Ireland after everything he’d said in favor of national self-determination while the treaty was being debated. Indeed, on his only trip back to the States from Europe in late February and early March, he said on arrival in Boston: ‘We set this Nation up to make men free and we did not confine our conception and purpose to America, and now we will make men free. If we did not do that all the fame of America would be gone and all her power would be dissipated’.

The Boston Irish heard encouraging and hopeful words for their old, green sod before the treaty was finalised—but that rhetoric became hollow when Wilson sided with Britain in viewing the ‘Irish Question’ as exclusively an internal matter within what was then called the ‘United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland’. Between de Valera’s barnstorming tour and press interviews—he stayed in the U.S. until December of 1920—and the anti-league campaign, animosity took root and affected how Americans of Irish heritage would vote, especially in 1920.

|

|

Left: Advertisement published in the Butte Daily Bulletin from the Friends of Irish Freedom in opposition to the Leage of Nations. Right: Editorial cartoon titled 'they won't dovetail', showing Wilson trying to fit together the 'proposed constitution of the League of Nations' and the 'Constitution of the United States' as Uncle Sam looks on dissapprovingly from April 1919. (Images: Library of Congress)

Wilson’s grueling travel and talking schedule took its toll on the country’s leader. In Pueblo, Colorado on September 25, he collapsed, and a week later (after being rushed back to the White House) he suffered a serious, debilitating stroke. Wilson never again delivered a speech on behalf of the treaty—or any other subject. Indeed, the world would later learn that First Lady Edith Wilson handled a considerable amount of governmental business, away from public view and often without her husband’s knowledge, the last 17 months of his presidency.

About six weeks after Wilson’s stroke and while he was still confined to private quarters in the White House, the Senate formally voted on the treaty, complete with 14 reservations Senator Lodge, the principal opponent, attached to it. The administration told Democratic senators to oppose this version—and it failed to receive the required two-thirds vote. A second try at ratification also went down to defeat, followed four months later (March 19, 1920) by another (and final) legislative attempt. That, too, failed, with the Treaty of Versailles and Wilson’s dream of the United States leading his envisioned League of Nations now officially dead.

The hackneyed axiom that one person can make a difference contains a certain amount of truth—both of a positive and of a negative nature. In Wilson’s case, he thought he could act alone on the world stage, and he disregarded any involvement of Republican senators at the Paris Peace Conference, even though they had assumed the majority in January of 1919. In addition, the president of Northern Irish heritage refused to provide any encouragement to the pleas for an independent Ireland that he received in Paris or in Washington. Finally, in submitting the treaty to the Senate, he rejected any of the proposed changes that might have satisfied ‘reservationists’ and resulted in ratification. Wilson, to be sure, made a large difference, and H.G. Wells noted what this political figure was really like when he amplified the passage quoted earlier in The Shape of Things to Come (1933): ‘the essential Wilson, the world was soon to learn, was vain and theatrical, with no depth of thought and no wide generosity. So far from standing for all mankind, he stood indeed only for the Democratic Party in the United States—and for himself. He sacrificed the general support of his people in America to party considerations and his prestige in Europe to a craving for social applause’.

In other words, the idealist was also an egotist, someone unwilling to work with others to translate his vision and words into action and institutions. He did win the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize for being (in the phrase of the Nobel Foundation) ‘Founder of the League of Nations’. A Nobel Prize might seem a noble consolation prize; however, he couldn’t find a way for his own country to become a member of the league he founded. He blamed the American Irish for what happened with the treaty, telling one historian: ‘Oh, the foolish Irish’, before adding; ‘would to God they might all have gone back home’.

Woodrow Wilson acted on his own throughout 1919. A century afterwards, one can see his failure of presidential leadership with an unblinkered clarity, and the responsibility for what happened—or what didn’t—lies with him alone.

Robert Schmuhl, Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Chair Emeritus in American Studies and Journalism at the University of Notre Dame and adjunct professor in the School of Law and Government at Dublin City University, is the author of Ireland’s Exiled Children: America and the Easter Rising (Oxford University Press, 2016). His most recent book, The Glory and the Burden: The American Presidency from FDR to Trump (Notre Dame Press) was published in September.