A New York state of mind: Éamon de Valera in Ireland’s global city

By Dr Darragh Gannon

‘It is a privileged honor, personal as well as official, to greet most cordially in the person of Éamon de Valera, the President of the Irish Republic. I do so officially as Chief Executive of the City of New York…[which calls] on me as Mayor to convey to him the welcome, in addition to the freedom, of the metropolis of the Western World, the City of New York’.

Éamon de Valera’s reception by Mayor John Hylan at City Hall on 17 January 1920 before a crowd of 1,000 New Yorkers bestowed upon the Manhattan-born Irish republican leader a political citizenship, and civic respectability, which belied his revolutionary career. Two months earlier, the prince of Wales had been afforded the same official recognition. De Valera’s 18 month residence, and political status, in the city of New York, created a significant forum for international recognition of the Irish Republic between 1919 and 1920. The ‘Empire City’ was a major hub for international media networks and interwar radical connections, while NYC’s five boroughs constituted the political capital of Irish-America. Saskia Sassen has defined such cosmopolitan centres of political power as ‘global cities’. ‘They are specific places whose spaces, internal dynamics, and social structure matter…global cities are not only nodal points for the coordination of processes, they are also sites of production…[by which] we may be able to understand the global order.’ Between June 1919 and December 1920, Éamon de Valera navigated the political spaces, internal dynamics, and social structures of New York, placing the ‘Irish Republic’ at the heart of both American and international affairs. New York, in effect, would become Ireland’s global city.

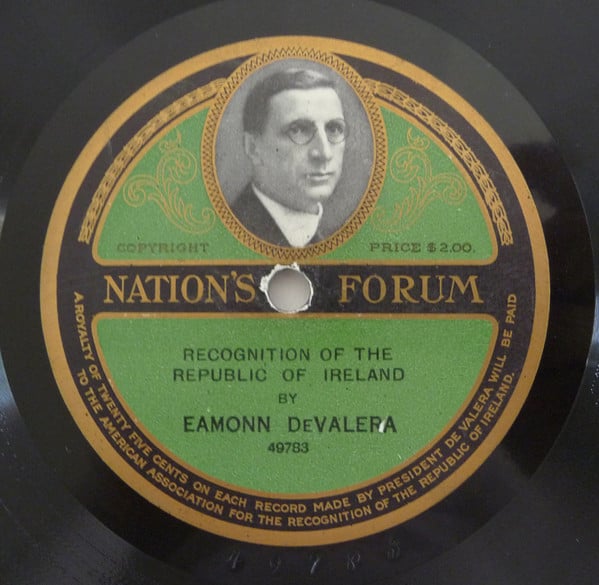

On 23 June 1919, the American-born ‘President of the Irish Republic’, Éamon de Valera, was unveiled to the world at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on New York’s 5th Avenue. It was a global media event. Over a thousand people thronged the hotel’s Astor Gallery to attend de Valera’s inaugural press conference, reporters arriving from Los Angeles to London. In a statement circulated to the press by ‘advance agent’ Harry Boland, de Valera declared: ‘from today I am in America as the official head of the republic established by the will of the Irish people in accordance with the principles of self-determination…we seek the aid of America…I feel that the American press will do its duty for me.’ Reflecting on de Valera’s New York première, IRB envoy to the US, Patrick McCartan, suggested that the Clan na Gael leadership, notably John Devoy, ‘had styled de Valera president of the Republic of Ireland. He had assumed that title. The press conceded it to him’. The New York media itself, however, would prove instrumental in shaping de Valera’s ‘presidential’ profile. Kathleen O’Connell, his newly assigned secretary, was immediately inundated with requests from the city’s leading journals for an interview with de Valera: New Republic, Current Opinion, The Nation. Meetings in his Waldorf Hotel suite were characterised by New York outlets as interviews with the ‘President of the Irish Republic’ in the ‘Irish White House’, accordingly. ‘The newspapers of this city have turned over a new leaf since Monday last’, one correspondent exclaimed to de Valera, ‘your arrival here at this time is a God send.’ The image of the ‘president of the Irish Republic’, further, attracted the publicists of ‘Madison Avenue’. In July 1919, de Valera was approached by the Nation’s Forum Record Label to contribute to its celebrated ‘Great Speeches’ LP series: ‘thus making it possible to project the voice and words of the President into every town, village and hamlet of the United States.’ De Valera later recorded three speeches in the Nation’s Forum’s 38th Street studio, joining John D. Rockefeller and Franklin D. Roosevelt, among America’s foremost recording artists. Offers of up to $50,000, meanwhile, were made from New York directors for the motion picture rights to de Valera’s life, leading to discussions of an early screenplay, and an acting role. New York City made the ‘president of the Irish Republic’ political box office.

Éamon de Valera LP

The central political space of Manhattan foregrounded the case for the Irish Republic. On 10 July 1919, the Friends of Irish Freedom hosted Éamon de Valera at a sold-out Madison Square Garden. A full 15,000 people packed the ‘Garden’ to see the ‘president of the Irish Republic’, while a further 10,000 waited outside, bringing the traffic on 7th Avenue to a standstill. De Valera’s eventual arrival on-stage was met with a 10-minute standing ovation. ‘This’, he proclaimed, ‘is New York’s recognition of the Irish Republic!’ News of Woodrow Wilson’s name being booed by the rapturous MSG crowd during the event would draw further attention to de Valera’s campaign in American political circles. Manhattan’s melting pot of ethnic communities, radical causes, and revolutionary activists, meanwhile, embedded the Irish Republic within a cosmopolitan anti-colonial counter-culture. De Valera would develop close ties with the Friends of Freedom for India during this period exchanging letters, literature, and political ideas with Indian nationalists such as Lala Lajpat Rai. In a February 1920 lecture later published as a pamphlet by that organisation, de Valera declared, ‘patriots of India your cause is identical with ours…you must act as we have tried to act…present [facts] in a form in which they can be readily grasped by the busy American’. Irish and Indian revolutionaries would share the stage with other New York-based nationalist groups, at the Lexington Avenue Theater, for the opening of the League of Oppressed Peoples. Further north (in Uptown), the case for the Irish Republic was advanced by Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. Garvey’s lectures at ‘Liberty Hall’, on West 138th Street, made common purpose with the republican movement: ‘I have a cable in my pocket that comes from Ireland that the Irish are determined to have liberty…we have a cause similar to the cause of Ireland’. Garvey, who assumed the title ‘Provisional President of Africa’, following de Valera’s New York campaign, further took to delivering messages of support for Ireland through a megaphone along Harlem’s Lenox Avenue. Elsewhere, Chinese, Egyptian, and Zionist nationalists were noted to be attending the Manhattan meetings of the Friends of Irish Freedom. Unlike the Wilsonian rhetoric of the republican mission in Paris, New York functioned as an ‘anti-imperial metropolis’ for Irish nationalists.

Over ‘the Bridge’, conversely, the cause of the Irish Republic was cultivated as a distinctly American question. Brooklyn branches of the Friends of Irish Freedom, which numbered 34 by July 1919, opened their events with the Star Spangled Banner, draped their platforms with the ‘Stars & Stripes’, and named branches after American patriots (‘Benjamin Franklin’ chapter). Its organisers, the FOIF declared, were ‘conversant with the particular needs of the borough’. This went beyond the ‘banal nationalism’ of anthems, flags, and titles. The Irish issue was integrated into the public spaces of Brooklyn’s social and political life. Block parties in aid of the Irish Victory Fund were co-hosted by the Friends of Irish Freedom and the local Democratic Party throughout the summer of 1919, gatherings featuring sidewalk lectures and pop-up clinics on the Irish Republic. Over 100,000 Brooklyn residents participated in block parties for ‘Irish Night’ on 12 August, from Sunset Park to Bedford-Stuyvesant. Flanked by the borough’s ‘prominent citizens’, meanwhile, de Valera would address the population of Brooklyn one month later: ‘Ireland has taken the lead in democracy by appealing direct to the American people for justice for her cause…I came to America to appeal to the plain people.’ Attempts to secure recognition for the Irish Republic, in greater New York, were grounded in the public spaces, and practices, of borough politics.

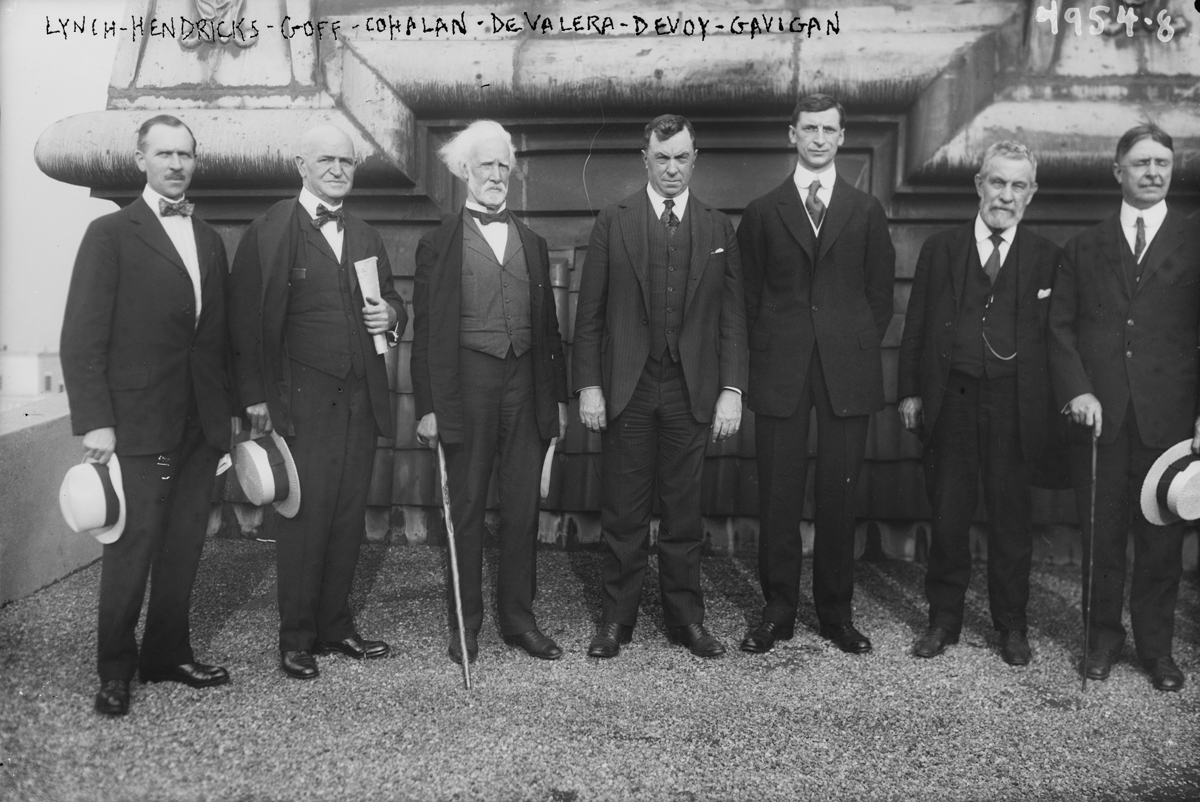

The New York clique with Éamon de Valera in 1919 (Image: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. USA)

New York also served as a nodal point for the coordination of Irish-American appeals to political power in Washington. The Friends of Irish Freedom were dominated by a group of high profile Tammany-style political leaders, namely New York Congressman Bourke Cockran, and Supreme Court judges Daniel Cohalan and John Goff. Collectively known as the ‘New York clique’, they alternated between FOIF meetings in NYC and Senate hearings in DC. Their collective objective, in the fall of 1919, was the defeat of the League of Nations and the achievement of Irish self-determination. Political opposition to the League, linked Irish-American district politics in New York to congressional politics in Washington, particularly in Cohalan’s borough of the Bronx. Here, the presidents of FOIF branches were invited to attend Senate Foreign Relations Committee sessions, members read transcripts of the hearings at local meetings, while candidates for Congress were presented by the Bronx FOIF with election questionnaires:

‘1. Are you in favour of the covenant of the League of Nations?

2. Do you believe that Ireland is entitled to a republican form of government?

3. Are you in favour of the Congress of the United States recognizing the Irish Republic?’

Addressing a Bronx rally against the League, attended by Cohalan, in October 1919, local Friends of Irish Freedom chairman James McGurrin declared: ‘We are asked to perpetuate conditions [in Ireland] by adopting Article X of the League of Nations. As American citizens we stand where we always have stood – America first.’ Speaking in the Bronx three months after the Senate defeat of the Treaty of Versailles, in February 1920, Éamon de Valera distanced himself from the Irish-American position: ‘so long as my countrymen are held in subjection by England, they will rise to aid any other nation that attacks Great Britain.’ The internal dynamics of Irish-American politics twinned the case for the Irish Republic in New York with the case against the League of Nations in Washington, without Éamon de Valera.

American recognition of the Irish Republic, moreover, could be achieved financially. Investing in the Dáil loan, according to the terms and conditions of the ‘bond’, was premised on an explicit acknowledgment: ‘the Government of the said Republic [is not] under any obligation to repay this sum…until the said Republic of Ireland is internationally recognized.’ The legality of the Dáil ‘bond’, therefore, underpinned the legitimacy of the Irish Republic. De Valera’s concerns that the loan would contravene US ‘Blue Sky’ laws (protecting the American public from fraudulent investment), was further undermined by the Wall Street Journal’s view: ‘sold as bonds, the de Valera issue is nothing more or less than a swindle.’ The social standing of New York’s Irish leadership, crucially, reinforced its respectability. Floated under the auspices of the American Commission on Irish Independence in January 1920, the reputability of the Dáil ‘bond’ was buttressed by the FOIF’s connections to the city’s legal system. The drive was launched with the endorsement of 40,000 New York state solicitors, while Bourke Cockran, who had the ‘reputation of delivering’ in American judicial affairs, served as the public face of the campaign. New York subscribers, consequently, would invest almost $1.5 million ($20 million in today’s money) in the ‘bond’. The political dynamics driving the ‘bond’ were in evidence in each borough, notably in Queens. Local FOIF branches organised canvassing committees according to voting districts, with ‘bond’ campaigns running from Long Island City to the ‘Irish Riviera’ of Far Rockaway. Community institutions such as schools, parish halls, and political clubs served as respectable assembly points for the sale of republican ‘bonds’; while local professionals such as city officials, judges, lawyers, and doctors were stated to be in attendance at meetings. ‘The Irish in this country live in mixed communities’ John Devoy noted of the FOIF’s vigorous ‘bond’ drive, ‘they have to be reached by special efforts.’ De Valera would later review the Queens campaign in Jamaica, Richmond Hill, Flushing and Astoria, by motorcar.

New York in 1920 remained the ‘swing state’ to Irish republican success in the US. The continued support of the New York leadership, de Valera strategised, would maintain the Friends of Irish Freedom as a political ‘instrument’ to coordinate the Irish-American ‘vote’. Cohalan’s New York caucus, further, provided the strongest ‘lever’ for securing American recognition of the Irish Republic – constitutionally, politically, and financially. De Valera, ultimately, however, would lose his political influence, and his base, in New York. His controversial February interview with the New York Globe, in which he made the case for British recognition of Irish independence on the lines of America’s geo-strategic relationship with Cuba, was exacerbated by a belated attempt to check the ‘America-first’ approach to Irish-American policy: ‘I am answerable to the Irish people’, he wrote to Judge Cohalan, ‘I alone am responsible…I may not blindly delegate those duties to anyone whatsoever’. Writing from the Gaelic American’s offices in Lower Manhattan, John Devoy contended de Valera’s argument: ‘[his] proposition comes to the Irish in America like a bolt from the blue…there is no good reason why Irishmen in America should not give their views.’ Privately, Devoy excoriated de Valera’s self-importance: ‘in New York, Brooklyn, Jersey our men are practically unanimous…his motto is “the King can do no wrong”.’ The break between Irish and American nationalists would determine de Valera’s political career in New York. Meeting in Midtown Manhattan (at the Park Avenue Hotel) on 19 March, 75 Irish-Americans, including the New York cabal of Devoy, Cohalan, Cockran, Judge John W. Goff, and Bishop William Turner, secretly convened the ‘trial’ of de Valera, without the latter’s knowledge. De Valera’s arrival midway through the proceedings prompted a blistering 10-hour exchange with Devoy and Cohalan, the latter charging that ‘de Valera would consult none; knew nothing of American history or politics; [and] alienated by his arrogance those who had spent a lifetime in Ireland’s service’. De Valera’s establishment of an Irish republican consulate at Beekman-Nassau St., on the doorstep of Devoy’s office, further distanced him from the Friends. Personal divisions in New York would result in a disastrous political split in Chicago, when de Valera and Cohalan submitted competing planks on Irish independence for consideration at the Republican Party Convention. Neither was accepted. ‘Big as this country is’, de Valera reflected, ‘it is not big enough to hold the Judge and myself’: synecdoche, New York. The establishment of the American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic in Washington DC in November 1920 would signify de Valera’s eventual departure from the ‘Tammany Hall’ politics of New York Ireland.

Between June 1919 and December 1920, New York served as Ireland’s ‘global city’. In the cosmopolitan streetscapes of Manhattan, the Irish Republic was made cause célèbre, attracting unprecedented international media, and internationalist revolutionary attention. Éamon de Valera’s US campaign, accordingly, was afforded the profile of a ‘president’. Attempts to secure American recognition of the Irish Republic, further, were significantly predicated on the constitutional, political, and financial leverage of New York Ireland. The political spaces, internal dynamics and social structure of Irish nationalism across New York integrated the Irish Republic into everyday American life, legitimising the political appeal for official recognition. De Valera’s differences with the Friends of Irish Freedom in New York, ultimately, undermined the potential to harness the power of Irish-America’s political capital. To paraphrase historian J.J. Lee: no New York, no America, no recognition of the Irish Republic.

Dr Darragh Gannon is Research Fellow to the AHRC-funded ‘A global history of Irish Revolution, 1916-1923’ at Queen’s University Belfast.