5 February 1922: Cumann na mBan Opposes the Anglo-Irish Treaty

Women Activists During the Civil War

By Marie Coleman

On Sunday, 5 February 1922, Cumann na mBan held a special convention in the Round Room of Dublin’s Mansion House to discuss the Anglo-Irish Treaty. A majority of those present (419 of 482, or 87 per cent) voted in favour of the motion by Mary MacSwiney (Sinn Féin TD for Cork Borough in the second Dáil) to reaffirm allegiance to the Irish Republic and reject the Treaty. Jenny Wyse Power’s counter-proposal that the organisation remain neutral was defeated.¹ Thus, Cumann na mBan became the first republican organisation to reject the Treaty.

During the Dáil debate on the Treaty in December 1921, MacSwiney had delivered one of the longest and most vehement speeches against it. Over the course of two hours and forty minutes she denounced it as a rejection of the republic ‘proclaimed and established by the men of Easter Week, 1916’, making particular reference to the opposition of the ‘women of Ireland’ to ‘the men that want to surrender’.² This illustrated a gendered division on the Treaty; MacSwiney was one of the six women TDs in the second Dáil, all of whom voted to reject the Treaty.

Among the reasons cited for the unanimity of the female TDs in voting against the Treaty was their close familial relationships to men who had died in the cause of Irish independence. Four of the six had lost close male relatives to violent or traumatic deaths.³ MacSwiney’s brother, Terence, died in October 1920 after a prolonged hunger strike. Two of Margaret Pearse’s sons, Patrick and William, and Kathleen Clarke’s husband, Thomas, were executed for their roles in the Easter Rising. Kate O’Callaghan’s husband, Michael, a former Sinn Féin mayor of Limerick, was shot dead in her presence in their home by Crown forces in March 1921.

To suggest that female political opposition to the Treaty was predicated on the importance in the republican pantheon of these women’s husbands, brothers and sons, negates the significance of their own political ideology. Their activities to that point, and their subsequent political careers, illustrate their own personal commitments to republicanism. Kathleen Clarke belonged to a family of noted republicans with links to the Fenians, and during her terms of office as the first female lord mayor of Dublin (1939–41) she refused to wear the mayoral chain because of its links to William of Orange. Although a close friend of Éamon de Valera, Mary MacSwiney was never reconciled to his new Fianna Fáil party or to the legitimacy of the independent Irish state. Two of the six women TDs—Dr Ada English and Constance Markievicz—did not have any male relatives fighting for Irish independence, further undermining the notion of female political opposition to the Treaty being based on such personal relationships.⁴ The minority of women who supported the Treaty re-convened under a new organisation named Cumann na Saoirse. Though lasting only until 1923 and not as active as Cumann na mBan during the civil war, Cumann na Saoirse demonstrated ‘that not all Irishwomen rejected the Treaty’.⁵

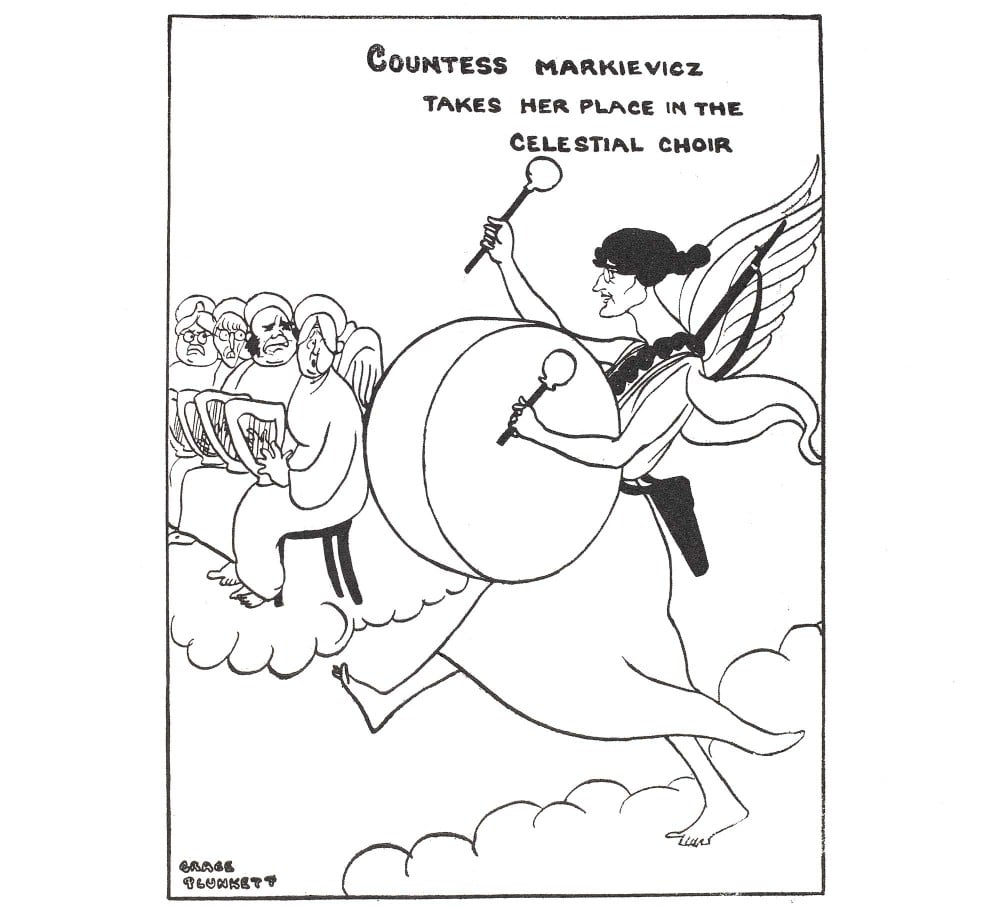

Depiction of Countess Markievicz by artist and anti-Treaty republican activist Grace Gifford Plunkett, 1927 (Image: NLI, ‘To hold as ’twere’: 17 caricatures, BB5554; courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

The activities of Cumann na mBan during the civil war largely mirrored those the organisation had engaged in during the War of Independence. Applications for military service pensions detail how women secured and transported arms and ammunition for the IRA and catered, provisioned and offered safe houses for men on the run. Although not involved in actual direct combat, the military-related activities of women exposed them to serious danger; in November 1922 Margueritte (Fleming) Sinnott travelled about a mile across country while under fire from the National Army in order to re-supply the local IRA unit with ammunition for an ambush.⁶

Most of these women were active where IRA resistance to the Irish Free State was strongest, including Dublin, Munster and the west. A small number were active in Northern Ireland, assisting the cross-border campaign of Frank Aiken’s division. Annie (Keelan) Maguire used her Dundalk base to transmit despatches from Dublin to the northern IRA, hid arms in the Sperrin mountains, raised funds for prisoners’ dependants and oversaw intelligence operations that resulted in the rescue of republican prisoners from Dundalk prison, prior to her arrest in Northern Ireland and deportation back to the Free State.⁷

Cumann na mBan’s former comrades-turned-adversaries had few illusions about the significance of their role in the republican campaign and as a result a significant number were arrested and imprisoned; at least five hundred women and girls were incarcerated, most of them in Dublin’s Mountjoy and Kilmainham jails and the hastily re-purposed North Dublin Union workhouse, where sanitary conditions and facilities were primitive.⁸

A valuable insight into the Kilmainham female prisoners’ political ideology and derisive attitudes towards their captors exists in the extant graffiti on the jail’s (now museum) walls and in surviving autograph books, a topic explored further in the following essay.⁹ The poor conditions experienced by women prisoners and the experience of some in undertaking lifethreatening activities, such as hunger strikes, often impaired their subsequent health. Following her release from prison in May 1923 Eilish McNamara continued to suffer from bronchial problems for a further two years; while in 1951 Nora Gavin was diagnosed as being in ‘an advanced state of nervous exhaustion’ arising from the trauma she experienced during the revolutionary years.¹⁰

Many women faced challenges in convincing pension assessors of the validity of their claims for military service and disability pensions. This attitude arose in part from hostility within the Free State to the strength of Cumann na mBan’s anti-Treaty stance and was most obvious in the initial refusal of a pension to Margaret Skinnider, ostensibly on the grounds that as a woman she did not adhere to the legislative definition of a ‘soldier’, but also because she was ‘a prominent irregular’.¹¹ The predominance of women on the republican side resulted in fewer women TDs in the Dáil in its early years because of the refusal of republicans to take their seats, and a misogynistic backlash from treatyite commentators such as P.S. O’Hegarty, who dismissed the women TDs who voted against the Treaty as ‘furies’.¹² This negative attitude towards women infused the restrictive role envisaged for women in public life in the new state after 1922.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.